By: Iain Cowie

May 23, 2023

Well-being

Well-being is a concept that has been studied extensively in the social sciences, but interestingly, there is still a great degree of uncertainty and ambiguity to the concept as an exact definition has been difficult to pin down. In fact, even the correct spelling of well-being (wellbeing) is a subject of uncertainty. This problem of definition has led to largely descriptive and overly broad understandings of well-being as a concept. Compounding this, wellbeing is often used interchangeably with concepts like quality of life, life satisfaction, or simply, happiness.

Because of its dynamic and multi-dimensional nature, well-being presents challenges for researchers, not only in definition, but also in scale and measurement. Well-being can be measured at a community or national scale using standardized economic, social, and environmental indicators. An example of this is the Canadian Index of Wellbeing (CIW) which measures wellbeing using 64 indicators across 8 domains. However, well-being can also be assessed on an individual basis using subjective measures revolving around positive and negative affect, happiness, satisfaction with life, and fulfillment.

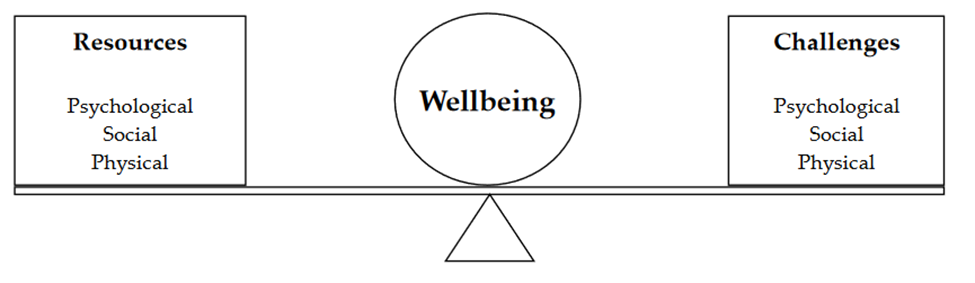

For my forthcoming Master’s thesis, I adopted a conception of well-being proposed by Dodge and colleagues (2012) that interprets well-being at the individual level as a dynamic state that fluctuates according to challenges and personal resources. This conception of well-being as a dynamic state implies the idea of an equilibrium which is comprised of personal life experiences and challenges as well as the resources that people use to cope with challenges and maintain equilibrium. As such, Dodge and colleagues’ definition of well-being is described as “the balance point between an individual’s resource pool and the challenges faced” (Dodge et al., 2012, pg. 230). This is illustrated using an analogy to a seesaw in which well-being is situated between personal resources (stocks) on one end, and challenges (flows) on the other. When the individual has more challenges than resources to cope with them, and vise versa, the seesaw will dip, representing a change in their dynamic state of well-being.

(Dodge et al., 2012, pg. 230)

Outdoor Recreation During Covid-19

My Master’s thesis research focuses on the impacts that outdoor recreation and green space exposure have had on health and well-being in the Westman region in Manitoba during the Covid-19 pandemic. For this project, a literature review was conducted to identify definitions of well-being, mental health impacts of Covid-19, the connections between outdoor recreation, physical activity, and exposure to nature, as well as emerging literature on outdoor recreation and park visitation during the pandemic. A survey was distributed in the Spring of 2021 assessing the outdoor recreational activities of individuals in the Westman region and the impacts that these had on respondents’ overall health and well-being. The survey included questions relating to the perceived impacts of Covid-19 on respondents’ well-being before and during the pandemic, respondents’ involvement in outdoor recreational activities (type, frequency, duration, number of park visits, etc.), and views concerning the role of outdoor recreational activities and green space exposure relative to well-being.

Some Key Take-aways from Survey Responses:

- Respondents reported increased feelings of nervousness (50%), sadness (51.3%), and being worn out (66.3%) during the pandemic.

- 37.5% of respondents engaged in outdoor recreational activities more frequently than before the pandemic, and 36.3% visited parks or green spaces more frequently.

- 66.5% of respondents reported high levels of well-being. 46.3% reported their overall health and well-being as good, 20% very good, while 27.5% reported moderate, and only 6.25% reported poor overall health and well-being.

- However, 55% of respondents indicated that they would describe their overall well-being as bad (32.5%) or very bad (22.5%) had they not had the opportunity to engage in outdoor recreational activities during the pandemic.

- 72.2% of respondents indicated that they view outdoor recreational spaces as more important to them personally than they did before the pandemic, 78.5% view them as more important for society, and 96.2% felt that more investments should be made to outdoor recreational spaces like parks, trails, and wildlife areas.

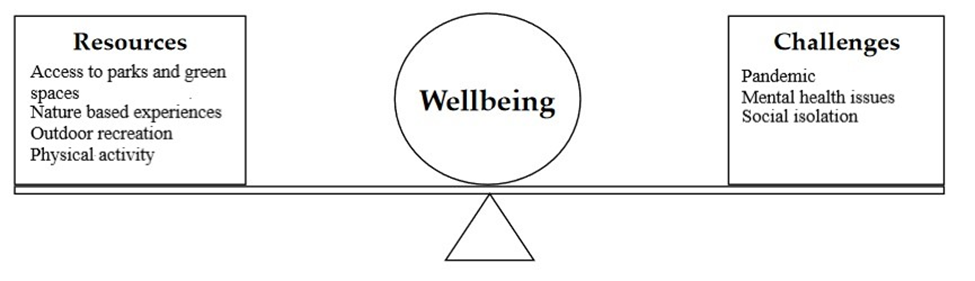

Dodge and colleagues’ conception of well-being can be applied to outdoor recreation and green space exposure as well as the challenges that people experienced throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. In this context, the challenges are represented on the seesaw by the pandemic itself as well as the various impacts that it had on mental health and well-being (e.g., Stress, anxiety, social isolation), while the resources include access to parks and green spaces, outdoor recreation, nature-based experiences, and physical activity.

(adopted from Dodge et al., 2012, pg. 230 – edited by the Iain Cowie, 2022)

This research provides evidence of the impact that outdoor recreation and nature exposure have had for maintaining well-being for residents in Westman. Green spaces have provided critical infrastructure that has helped facilitate these opportunities during the Covid-19 pandemic. This forthcoming research offers insights and recommendations regarding the importance of these spaces as resources for maintaining well-being during future societal shocks and challenges.

References

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

Dodge, R., A.P. Daly, J. Huyton and L.D. Sanders (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing.

International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222-235.

Canadian Index of Wellbeing. (2016). How are Canadians Really Doing?

The 2016 CIW National Report. Waterloo, ON: Canadian Index of Wellbeing

and University of Waterloo.